Armed Forces

Babcock: Technology transfer is what we do [INTERVIEW]

All of the additional equipment Poland wants can easily be fitted into the ship - as John Howie, Chief Corporate Affairs Officer, Babcock International told Defence24.pl in an interview. He also mentions Babcock’s industrial cooperation offer for Poland.

Jakub Palowski: Babcock International has large experience in industrial projects, but not necessarily in warship construction. During the past years, Babcock participated in the construction of two carriers for the UK Royal Navy within the Aircraft Carrier Alliance (along with BAE, Thales, and MoD UK), 4 VARD-design based OPVs were delivered to Ireland as well. However, Babcock has not built frigate-class ships, or similarly complex warships independently. The Type 31 frigates that are being built for Britain are at an early stage and they will be less sophisticated than the Polish ships (less sensors, subsystems). The Polish Miecznik will be much more complex than Type 31 and they will be built in the Polish shipyards, PGZ, which face structural issues. Are you afraid that the limited experience of Babcock in frigate-class projects and technology transfers may affect the risks of Miecznik project?

John Howie, Chief Corporate Affairs Officer, Babcock International: Actually, technology transfer is what we do. I have been in shipbuilding for 25 years and, in my experience, industry often talks of technology transfer but almost never does it. There can be a tendency to keep technologies within businesses. Some of the shipyards that we have competed against are state-owned - there are plenty of them in Europe - which means they are generally expected by their governments to do as much work in their own countries and to employ local people.

That is not our business model; our business model assumption is always to build the vessels in country. So, technology transfer is the key. I will give you three specific examples of where we have delivered large scale technology transfer recently. We are contracted to support the Canadian Navy submarine fleet. When Canada bought four submarines, [ed. Upholder in Britain and Victoria in Canada], there was little in-country infrastructure, experience or supply chain to maintain and operate submarines.

We built our business alongside our customer, creating a team of 450 qualified submarine-capable engineers, a supply chain, infrastructure, and a set of fully-operational submarines, because we invested in Canada - we invested a hundred percent of our contract value in Canada. In Australia, we transferred the technology to maintain and support the weapons’ launch system on the Collins-class submarines. It is fully supported in Australia; it doesn’t come back to UK. We have also built the capability to refit the ANZAC-class frigates by transferring those skills from both Rosyth and Devonport in the UK. We have done the same in New Zealand. Each time, we have built a business, recruited local people, given them highly skilled jobs and development opportunities and created or strengthened a capability.

Right now, we are in the process of building a software development team in Australasia that can develop control systems for highly complex defence communications systems. So, I would say actually, that we are one of the best at technology transfer because when we say we are going to do it, we actually do it.

The PGZ shipyards need substantial support as they face some issues, are you confident that you would be able to cooperate with them?

I don’t want to make a detailed comment about PGZ. What I can say is that Poland is in the process of defining how it revitalizes its shipbuilding industry. We have been a central part of that same process here in the UK. We have built a world-class shipbuilding capability here in Rosyth. We have got equipment and systems that are used in less than a handful of yards in the world. We have that capability now and we built that from a standing start in about 15 months. That’s the experience that may help PGZ.

I wouldn’t worry about the PGZ you may think you see today. Part of the UK’s offer to the Polish government and PGZ is to stand side by side with them all the way through this contract, to ensure that the right infrastructure, right skills and right technology are in place. And that is because, as I said earlier, we want to be in Poland as a Polish business, not as a British business in Poland; it is important to see the distinction.

Will you be able to transfer the technology of Air Defence frigates, despite the fact that Type 31 project was launched just recently, and it is a less sophisticated vessel than the Miecznik as we see it?

We have designed and are building five frigates; today Type 31 is progressing well. We also had an integral role in the project that delivered the two aircraft carriers. Those are the world’s only fifth-generation aircraft carriers. 65,000 tons, highly complex, huge air integration challenges. We did more than half of the design of those ships, we built large parts of the structure and we did all the assembly and parts of the integration. This is the capability that allowed us to demonstrate to the Royal Navy why we should build the new Type 31 frigates.

And it is worth remembering that the Royal Navy is a top-class customer. They may not be the biggest navy in the world, but remain one of the most technically respected, and we have demonstrated to them that we not only have the ability to design and build and integrate frigates, but to do so in a way that is genuinely innovative; world-class. I have been involved in the construction of the Type 23 frigates for the Royal Navy, as well as the process of building the Type 45 destroyers, aircraft carriers, landing craft and offshore patrol vessels for the Irish Navy. We go into this with the relevant experience.

So, while there are a lot of people that have been building ships the same way for a long time, what we offer Poland is to jump ahead of some of those yards and to build ships in a way that will be competitive in the world market. We can do certain things in minutes because we have invested in automation, while in other yards it may take days or weeks. That is the benefit of our investment in innovation.

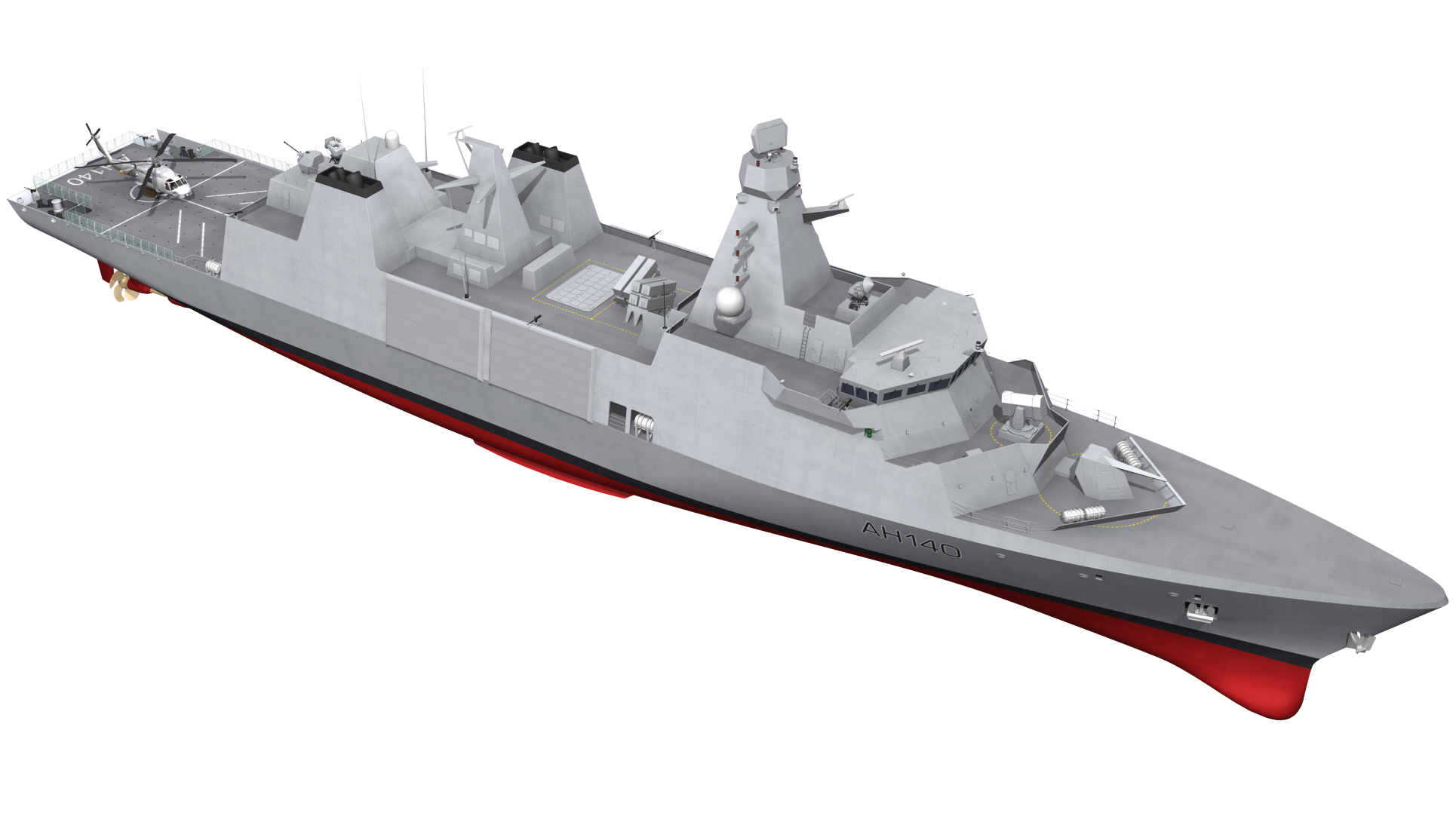

Let me move to the specifics of the Polish project. What are the major features of Arrowhead 140PL and the major differences between AH140PL and Type 31? It seems that the Polish frigate will be a little bit more sophisticated.

I think that in general I see the specification of the Polish combat system around the Miecznik frigate as quite high and we understand why that is. I don’t think it would be appropriate for me to go into details due to commercial confidential agreements on what equipment the Polish Navy would like to see installed.

What I can do is talk in general about the features of Arrowhead 140 and why it is suitable for the Polish variant. One of the things about the Arrowhead 140 that makes it a very good project for the revitalization of shipbuilding in Poland is the fact that Arrowhead 140 is the most production-engineered warship design I have ever seen in my career.

It has been designed from the beginning in such a way that it makes it easy to build. It is very flexible and has a lot of space; the machinery spaces are enormous. It is pretty easy to maintain and relatively simple to build. And if you want to take the shipyard through that journey of rebuilding a capability, what you don’t want is a frigate that has been designed in a such way that it is very difficult to build. And that is why AH140PL is a good option. And the space the ship has means that all of the additional equipment Poland wants can easily be fitted into the ship. It doesn’t affect the ship’s key performance characteristics and there will still be space for upgrades.

Czytaj też: Poland Signs Agreement for Miecznik Frigates

How about the aerial platforms? Poland has just recently bought AW101 maritime helicopters, but procurements for lighter manned helicopters and UAVs are underway. Will Miecznik AW140PL be able to handle heavier helicopters?

The ship could land a Chinook helicopter on the aft deck. The hangar is large enough to take Leonardo AW101, called Merlin in the UK. We model lots of helicopter scenarios, it could also be Seahawk, or a lighter helicopter like Wildcat or H160. Alongside, we could take a lot of unmanned systems. It’s a big hangar.

On the sides of the ship, you can accommodate the 11–12-meter long RHIB or deployable patrol boats. Right in the middle of the ship you can mount a Vertical Launch System, like Mk 41. This is part of our design feature, a lot of ships have VLS in the front, which makes the front heavier. Placing the VLS in the middle is better for the balance of the ship. You can place a lot of missiles there, including the Air Defence missiles that Poland recently made an announcement on.

In the Polish configuration the hull will be strengthened because it will need to withstand the adverse weather and the ice. There will be other changes made to reflect the normal operating model of the Polish Navy. But fundamentally, the key thing that will change is that every customer for the warship chooses their own combat system, the sensors, and the effectors. So, the Combat Management System will be chosen by the Polish Ministry of Defence, and the weapons that connect to that CMS will be of customer choice.

Does that include also medium- or long-range Air Defence missiles, besides the short-range missiles, that you have mentioned and are already planned on the Type 31?

Combat Management Systems, weapons and sensors are always of the customer’s choice, that includes the Polish-made sensors. Let me move to the CMS a bit. Type 31 has Thales TACTICOS. Why did we choose TACTICOS? Because TACTICOS is an open architecture system, and the thing that often goes wrong with the complex warship programs is the functional integration between the CMS and a gun, a missile system, a radar and an electro-optic device, the way TACTICOS is designed is relatively simple, you have an interface (black box) between the two pieces of equipment.

By the time we chose the main equipment for Type 31, TACTICOS was being used on over 130 ships around the world, and there was only one main piece of equipment to be included that had not been integrated in TACTICOS which meant our CMS risk was really low. Of course, the Polish MoD can also choose other solutions, such as the American Aegis system, which is a much more controlled environment, or the Saab system; there is a lot of choice to choose from.

The choice of CMS would influence the layout of the ship, the space and compartments, chilled water needed, shape of the mast arrangement it will include, and the magazines, but what we have demonstrated with AH140, is that we can accommodate any of the options the Polish MoD might choose, without impacting on performance, stability and incorporate all the requirements that the Polish Navy are looking for. As for the missile system, this is the customer’s choice, but a commonality used between the Ground Based Air Defence and the Naval Air Defence would be a logical choice. And, yes, of course, we can also integrate longer range missiles; as I said this is up to the customer.

Czytaj też: Narew SHORAD Still a Go [COMMENTARY]

The Polish Miecznik program assumes that the Polish industry, namely PGZ, will be the leader (prime contractor) of the project. You already spoke on the technology transfer, but have you engaged with the Polish side, on the division of responsibilities? It seems important, as you could be delivering lots of technology, and schedules are important.

We have a very clear view with PGZ on “who does what” and it would be hard for us to write our proposal without that. We have spent a lot of time thinking about how that would work. One of the key elements of our proposal is technology transfer; it is not just about selling a platform design license and providing some of the engineering support. We are willing to be risk-sharing and mentor every part of the program, right through to the vessel acceptance.

We have a clear view on how we will deliver what the Polish Government is asking for. We have also clearly indicated that we are ready to take a substantial share of risk as a result of the confidence we have both in the shipyard design and the platform design that we will help to implement.

Besides PGZ, there will be numerous other companies included, including the Remontowa Shipbuilding. Have you started the creation of a Polish supply chain for the frigate program? To what extent is the Polish industrial participation possible?

We have started to work on that. If Arrowhead 140 is chosen as the basis for Miecznik, as the preferred design, there will be a period when modifications will be added to the baseline AH140PL to include all the changes, systems, and sensors that Poland wants. That period may take a bit more than a year until we cut steel. During the process we will work with the Polish supply chain to maximise the amount of revenue that is provided to the Polish economy. We understand the importance of engaging a Polish supply chain to the greatest possible extent. Shipbuilding is a core part of national prosperity and in the UK we know that very well.

There will be some elements that are unlikely to be sourced in-country, such as the main diesel generators, shaft line propellers etc. For some of the other systems, I don’t see any reason why Polish suppliers that have a long and really positive history in the maritime industry wouldn’t be able to have a role in the programme. And we would aim to bring them into the supply chain in cooperation with PGZ.

Miecznik program is the largest major shipbuilding project of the Polish Navy that is currently planned. To achieve a good return for the substantial investments made in the project, the Polish shipyards will need other revenue sources. What is the way you could support them, beyond the Miecznik project?

As I said earlier, our aim is to build Babcock in Poland. We are seeking a long-term partnership. And that is why, as part of our proposal, we plan to invest alongside PGZ. Once Poland has built these frigates using the optimalisation methods and processes we will help to implement as part of this contract, I don’t see any reason why those same shipyards wouldn’t be successful in export markets. Potentially Babcock and PGZ could work in partnership.

Also, there could be another option, since Babcock is bidding and exploring other contracts around the world and we are always looking for good long term supply chain partners. What I have seen in PGZ is a company that I would be happy to work with. We don’t see the frigate programme as a one-off; we see it as the start of a longer-term relationship. And that is what makes the Babcock solution particularly advantageous for Poland.

Let me move to general Babcock business for a while. Babcock has quite recently posted a loss in its financial statements, there were also some redundancies. How do you think it could influence the capability of Babcock in the Miecznik program, were some of the losses related to the civilian business?

First of all, I would like to comment on the financial statements. We wrote down a number of intangible assets in the balance sheet, which is the process the new chief executive officer and new chief financial officer implemented, which is not unusual as part of business restructuring.

We have tidied our balance sheet in some of our sectors that are not related to shipbuilding. For example, we have a significant civil aviation fleet, one of the largest in Europe, doing firefighting and emergency response, MEDEVAC, and a lot of the balance sheet adjustment was getting that business to its fair value. Our core ship design and construction business is not really affected.

The maritime business of Babcock has traditionally been strong and that has not changed. Although there were some redundancies announced across the organisation, they are mainly related to streamlining the management structure. Over time, in large companies, the management layers can become larger and our aim is now to ensure that the distance between the senior management and people that actually build ships, for instance, is as short as possible. However, while we are doing that, we are still recruiting engineers, project managers, planners, estimators etc. The marine business is really strong and, for example, we have just received new important strategic contracts from the UK Government, such as a contract for high frequency radio communications, additionally, we have just won a contract to deliver new electronic warfare systems for the Royal Navy, which we will deliver in partnership with three other companies as we grow our footprint in more sophisticated high-end programmes.

Babcock recently said that the AH140 concept design was recently sold to Indonesia. How can the Polish and Indonesian frigate projects, and Babcock’s offerings for respective countries be compared? Are there any other prospective markets for Arrowhead?

I would say that we are offering a very good value for money frigate design, perhaps the most competitive in NATO. So, despite a perception that Type 31 may not be a complex ship, it is actually a more complex warship than the Type 23 it replaces, more heavily armed and more survivable. For Indonesia and Poland, we are offering the same solid, reliable design – a solid, 6000-ton frigate that we are selling to the Royal Navy for 250 GBP million; there are not a lot of frigates in the market that would get close to that pricing point. And it is all about the way it is designed to be easy to build and maintain, as well as flexible to modify.

Indonesia, like Poland, has its own view on the combat system, sensors and effectors, so the thing that will be different between the two ships would be the combat system layout, and any related changes to the overall design, but they will not affect the basic principles of the design of the ship; it will have the same length, engines etc.

Indonesia is also a technology transfer project; we are selling the license design for the AH140 to Indonesia’s PT PAL, and then we will help them in the engineering efforts for the build and integration. As a rule, we assume the vessels we offer will be built in-country and that is why the technology transfer plays a crucial role here. As for other markets, what I can say is that we have received more than 30 requests of interest regarding the project. We have a number of ongoing projects, but beyond the fact we are involved in Poland, Greece and, as you mentioned, Indonesia, I cannot give any more details. As the Type 31 progresses, the interest will only grow.

So finally, how is the Type 31 project progressing?

Type 31 is progressing very well. We signed the contract around two years ago and during that period we have met every major milestone either on time or early. Bear in mind that we are still running ahead of schedule despite the fact that the UK was locked down for five months because of COVID. It is actually ahead of schedule now.

We have done the Whole Ship Critical Design Review. This is an independent assessment to make sure that the design is mature. We brought in a team of independent experts we trust to tell us what we need to know and not what we would like to know, and this was a really complex review, which was passed with a small number of minor observations, nothing major. We cut steel ahead of schedule. We are progressing with various parts of the warship and we are on track to have the first frigate in the water in 2023, two years from when we started building.

Thank you for the conversation.

BUBA

Co prawda Anglia kroluje na morzach i oceanach ale ja stawiam na niemieckie Fregaty i U212CD ...